This guest post was written by Jean de Klerk, Developer Program Engineer, Google

Much of the web today runs on HTTP/1.1. The spec for HTTP/1.1 was published in June of 1999, just shy of 20 years ago. A lot has changed since then, which makes it all the more remarkable that HTTP/1.1 has persisted and flourished for so long. But in some areas it’s beginning to show its age; for the most part, in that the designers weren’t building for the scale at which HTTP/1.1 would be used and the astonishing amount of traffic that it would come to handle.

HTTP/2, whose specification was published in May of 2015, seeks to address some of the scalability concerns of its predecessor while still providing a similar experience to users. HTTP/2 improves upon HTTP/1.1’s design in a number of ways, perhaps most significantly in providing a semantic mapping over connections. In this post we’ll explore the concept of streams and how they can be of substantial benefit to software engineers.

Semantic mapping over connections

There’s significant overhead to creating HTTP connections. You must establish a TCP connection, secure that connection using TLS, exchange headers and settings, and so on. HTTP/1.1 simplified this process by treating connections as long-lived, reusable objects. HTTP/1.1 connections are kept idle so that new requests to the same destination can be sent over an existing, idle connection. Though connection reuse mitigates the problem, a connection can only handle one request at a time – they are coupled 1:1. If there is one large message being sent, new requests must either wait for its completion (resulting in head-of-line blocking) or, more frequently, pay the price of spinning up another connection.

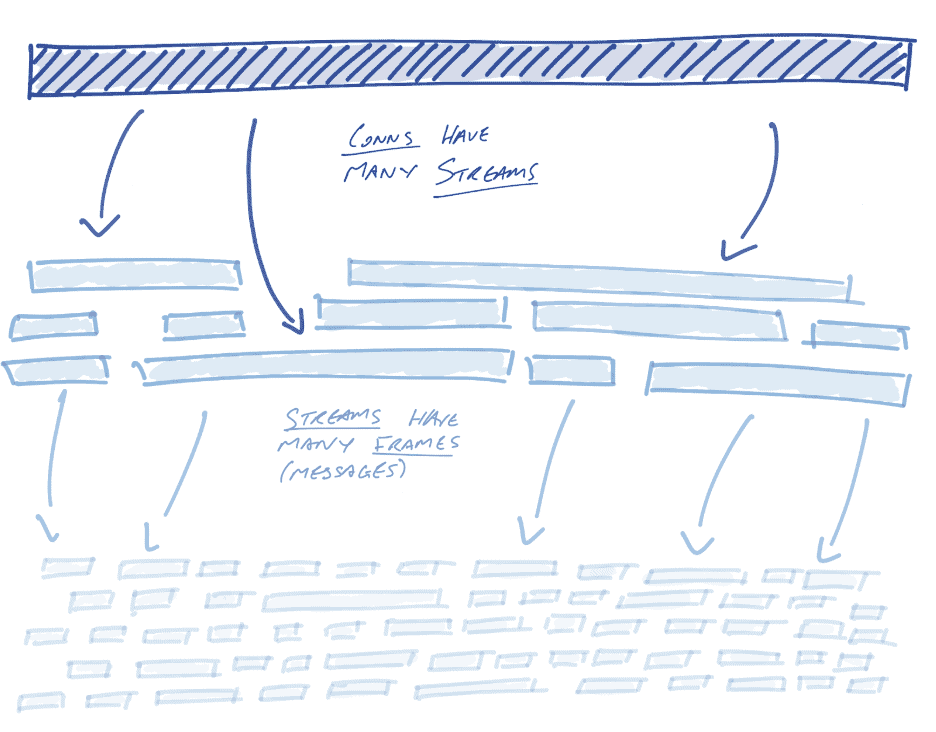

HTTP/2 takes the concept of persistent connections further by providing a semantic layer above connections: streams. Streams can be thought of as a series of semantically connected messages, called frames. A stream may be short-lived, such as a unary stream that requests the status of a user (in HTTP/1.1, this might equate to `GET /users/1234/status`). With increasing frequency it’s long-lived. To use the last example, instead of making individual requests to the /users/1234/status endpoint, a receiver might establish a long-lived stream and thereby continuously receive user status messages in real time.

Streams provide concurrency

The primary advantage of streams is connection concurrency, i.e. the ability to interleave messages on a single connection.

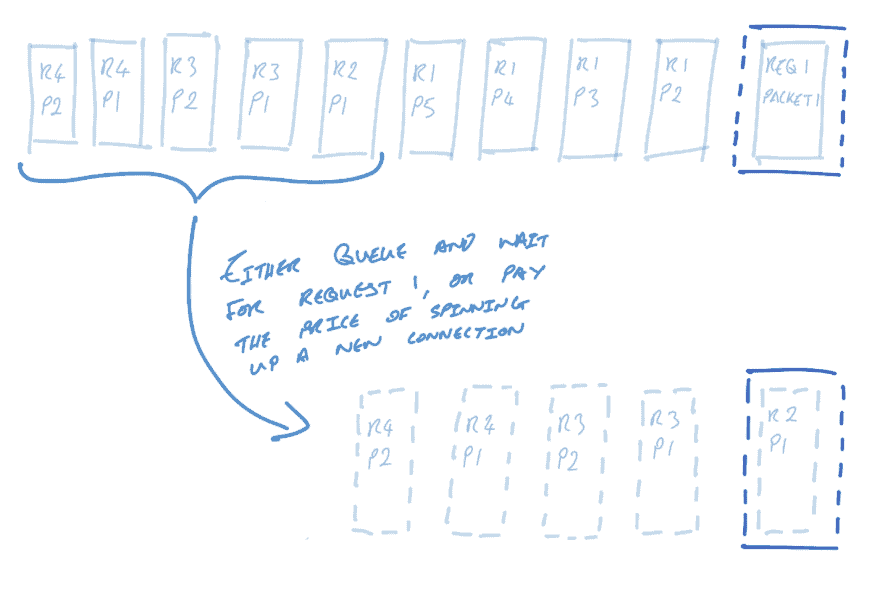

To illustrate this point, consider the case of some service A sending HTTP/1.1 requests to some service B about new users, profile updates, and product orders. Product orders tend to be large, and each product order ends up being broken up and sent as 5 TCP packets (to illustrate its size). Profile updates are very small and fit into one packet; new user requests are also small and fit into two packets.

In some snapshot in time, service A has a single idle connection to service B and wants to use it to send some data. Service A wants to send a product order (request 1), a profile update (request 2), and two “new user” requests (requests 3 and 4). Since the product order arrives first, it dominates the single idle connection. The latter three smaller requests must either wait for the large product order to be sent, or some number of new HTTP/1.1 connection must be spun up for the small requests.

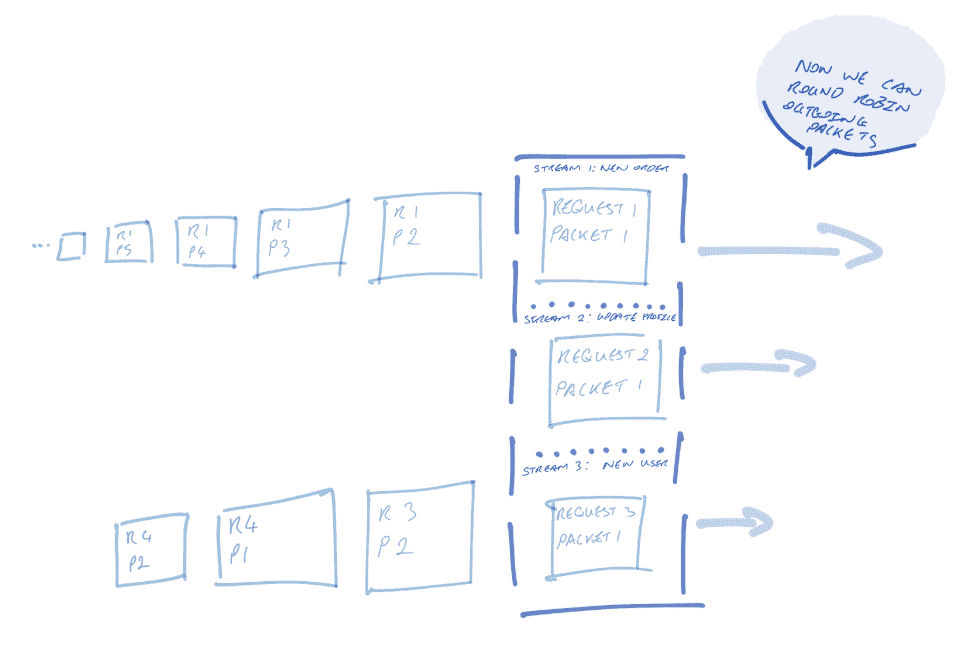

Meanwhile, with HTTP/2, streaming allows messages to be sent concurrently on the same connection. Let’s imagine that service A creates a connection to service B with three streams: a “new users” stream, a “profile updates” stream, and a “product order” stream. Now, the latter requests don’t have to wait for the first-to-arrive large product order request; all requests are sent concurrently.

Concurrency does not mean parallelism, though; we can only send one packet at a time on the connection. So, the sender might round robin sending packets between streams (see below). Alternatively, senders might prioritize certain streams over others; perhaps getting new users signed up is more important to the service!

Flow control

Concurrent streams, however, harbor some subtle gotchas. Consider the following situation: two streams A and B on the same connection. Stream A receives a massive amount of data, far more than it can process in a short amount of time. Eventually the receiver’s buffer fills up and the TCP receive window limits the sender. This is all fairly standard behavior for TCP, but this situation is bad for streams as neither streams would receive any more data. Ideally stream B should be unaffected by stream A’s slow processing.

HTTP/2 solves this problem by providing a flow control mechanism as part of the stream specification. Flow control is used to limit the amount of outstanding data on a per-stream (and per-connection) basis. It operates as a credit system in which the receiver allocates a certain “budget” and the sender “spends” that budget. More specifically, the receiver allocates some buffer size (the “budget”) and the sender fills (“spends”) the buffer by sending data.The receiver advertises to the sender additional buffer as it is made available, using special-purpose WINDOW_UPDATE frames. When the receiver stops advertising additional buffer, the sender must stop sending messages when the buffer (its “budget”) is exhausted.

Using flow control, concurrent streams are guaranteed independent buffer allocation. Coupled with round robin request sending, streams of all sizes, processing speeds, and duration may be multiplexed on a single connection without having to care about cross-stream problems.

Smarter proxies

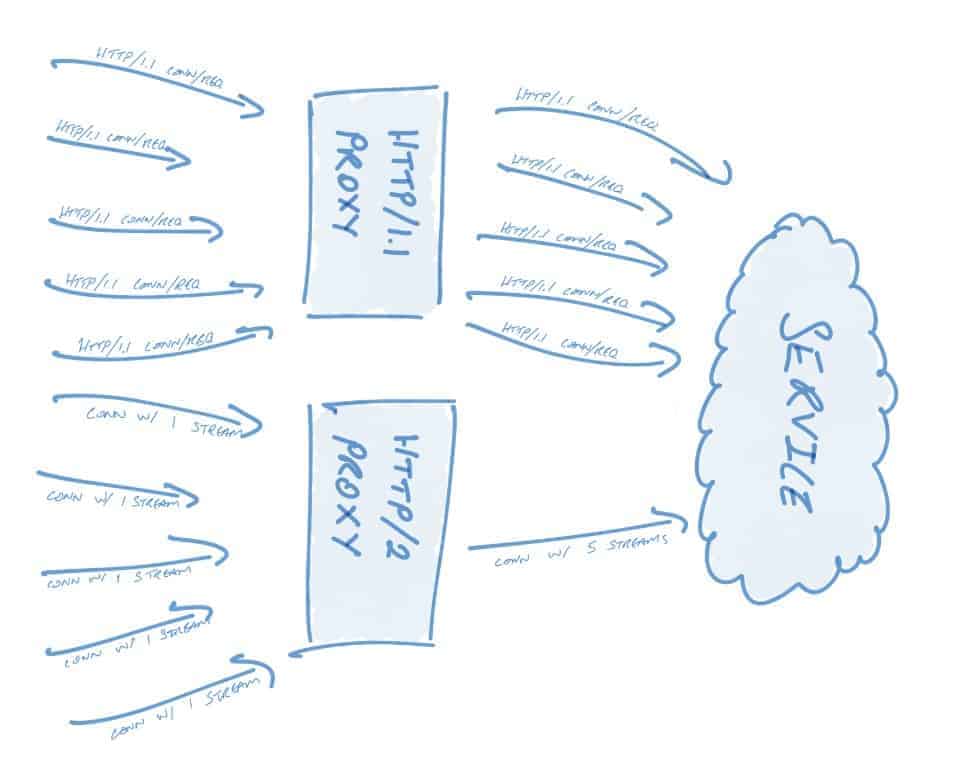

The concurrency properties of HTTP/2 allow proxies to be more performant. As an example, consider an HTTP/1.1 load balancer that accepts and forwards spiky traffic: when a spike occurs, the proxy spins up more connections to handle the load or queues the requests. The former – new connections – are typically preferred (to a point); the downside to these new connections is paid not just in time waiting for syscalls and sockets, but also in time spent underutilizing the connection whilst TCP slow-start occurs.

In contrast, consider an HTTP/2 proxy that is configured to multiplex 100 streams per connection. A spike of some amount of requests will still cause new connections to be spun up, but only 1/100 connections as compared to its HTTP/1.1 counterpart. More generally speaking: If n HTTP/1.1 requests are sent to a proxy, n HTTP/1.1 requests must go out; each request is a single, meaningful request/payload of data, and requests are 1:1 with connections. In contrast, with HTTP/2 n requests sent to a proxy require n streams, but there is no requirement of n connections!

The proxy has room to make a wide variety of smart interventions. It may, for example:

- Measure the bandwidth delay product (BDP) between itself and the service and then transparently create the minimum number of connections necessary to support the incoming streams.

- Kill idle streams without affecting the underlying connection.

- Load balance streams across connections to evenly spread traffic across those connections, ensuring maximum connection utilization.

- Measure processing speed based on WINDOW_UPDATE frames and use weighted load balancing to prioritize sending messages from streams on which messages are processed faster.

HTTP/2 is smarter at scale

HTTP/2 has many advantages over HTTP/1.1 that dramatically reduce the network cost of large-scale, real-time systems. Streams present one of the biggest flexibility and performance improvements that users will see, but HTTP/2 also provides semantics around graceful close (see: GOAWAY), header compression, server push, pinging, stream priority, and more. Check out the HTTP/2 spec if you’re interested in digging in more – it is long but rather easy reading.

To get going with HTTP/2 right away, check out gRPC, a high-performance, open-source universal RPC framework that uses HTTP/2. In a future post we’ll dive into gRPC and explore how it makes use of the mechanics provided by HTTP/2 to provide incredibly performant communication at scale.