Guest post originally published on CloudOps blog by Alexandre Menezes, Service Reliability Engineer, Red Hat

Most applications will require resources from the environment they are running on. Memory, CPU, storage, networking, etc. Most of those resources may be consumed easily and transparently, some may not depending on the application. Most applications will require some previous configuration steps before being deployed and will require a few, or maybe a lot, of special maintenance tasks that may be related to backups, restores, file compression, high availability checks, log maintenance, database growth, and sanity routines, etc. They may need to be put into some special state while upgrading to make sure they won’t drop the users for example.

All those things we just described are the applied human technical knowledge on top of an application. All that operational toil is repeated multiple times during the lifecycle of a living and serving software. Of course many times they have a few scripts to automate those tasks. But what if that application lives and grows inside a container, in a Pod, orchestrated by Kubernetes or OpenShift? Is there a better way to automate all of that? Something that could “enable loosely coupled systems that are resilient, manageable, and observable. Combined with robust automation, they allow engineers to make high-impact changes frequently and predictably with minimal toil”? (from the Cloud Native Definition)

And the answer to this question is the operator pattern. A.k.a Kubernetes Operators. So what are they? How to develop one? What can they add to our applications? And how do they add up to our software as a service experience by publishing them to an operator hub?

The best definition I personally like to give is an operator is an extension to the Kubernetes API, in the form of a Custom Resource, reconciled/managed by a standard controller running in a Pod out of a Deployment. Seems complicated, right? Let’s check those parts:

Extending the Kubernetes API

First, let’s step back just a little bit and try to understand it piece by piece. The first question I would ask is how do we interact with Kubernetes? We use kubectl to deploy and maintain our application from a stand-alone admin perspective, we use client-go and other libraries to automate the communication with Kubernetes API. Ok cool. What does the API give to us?

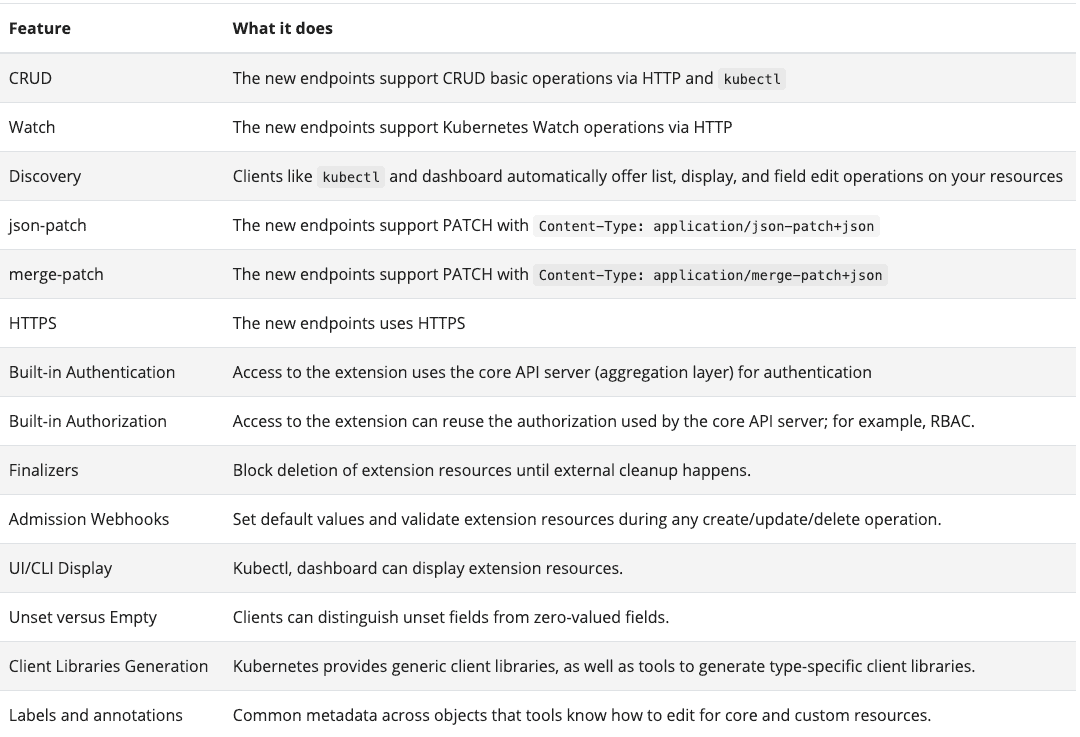

Let’s take a look at what the Kubernetes API gives to us:

All those features are shared between native Kubernetes objects. Many well-designed operations such as create, read, update and delete, the capability of watching endpoints, authentication and authorization, and much more.

We know that Kubernetes resources are built on top of definitions that come from the canonical Kubernetes API that lives in this repository: https://github.com/kubernetes/api

And there we can find the groups, the versions and kind for those resources, right? That is the information that goes straight in the field called TypeMeta. Let’s take a look at that!

If we get a resource such as a DaemonSet and run:

$ kubectl get DaemonSet myDS -o yamlIn the very beginning we’ll see something like below:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: DaemonSetThis is telling us that DaemonSets are under the group apps, has the version v1, and is a kind of DaemonSet. And where can we find the corresponding golang type for that object? We just need to navigate into that repository and find the types.go file. Like below:

$ tree -L 2

...

├── apps

│ ├── OWNERS

│ ├── v1

│ ├── v1beta1

│ └── v1beta2

...

Inside the folder v1 we have types.go and we can look for Type DaemonSet like below:

type DaemonSet struct {

metav1.TypeMeta `json:",inline"`

// Standard object's metadata.

// More info: https://git.k8s.io/community/contributors/devel/sig-architecture/api-conventions.md#metadata

// +optional

metav1.ObjectMeta `json:"metadata,omitempty" protobuf:"bytes,1,opt,name=metadata"`

// The desired behavior of this daemon set.

// More info: https://git.k8s.io/community/contributors/devel/sig-architecture/api-conventions.md#spec-and-status

// +optional

Spec DaemonSetSpec `json:"spec,omitempty" protobuf:"bytes,2,opt,name=spec"`

// The current status of this daemon set. This data may be

// out of date by some window of time.

// Populated by the system.

// Read-only.

// More info: https://git.k8s.io/community/contributors/devel/sig-architecture/api-conventions.md#spec-and-status

// +optional

Status DaemonSetStatus `json:"status,omitempty" protobuf:"bytes,3,opt,name=status"`

}

What if we can develop our application as being a native part of Kubernetes this way or at least leveraging all those features in such a way that we just type in kubectl get myapplication and receive back information based on my specific needs? And going further what if we can actually create our own update routines and functions? What if we could leverage the embedded metrics and build deep insights from Kubernetes the same way we do with native resources?

The cool features that share all that good stuff that Kubernetes provides are the Custom Resources and Custom Resource Definitions. They will behave pretty much like the native Daemonsets we saw before. They are extensions of the Kubernetes API that allow us to create our own fields crafting the perfect data structure to represent our application needs. They allow us to have our own api group, versions, and kind.

Here you can check more about CRDs and API extensions. But we’re half done here. What else do we need to put those Custom Resources to life? The controller. Let’s check it!

Controllers: Making it Kubernetes Native

Controllers are nothing else than a loop. The idea is a control loop that for each iteration it checks the state of some resource. After checking the state of the desired resource by reading it, the control loop runs what we call the reconcile function that compares that live state with the expected state for that given object. That’s the standard way Kubernetes works.

So, if we’ve defined our own custom object representing our application, with all fields and required data structures, the piece that comes after is this controller with its reconcile function. It really gives us control of the state of our application by running a custom logic that embeds the human operational knowledge we’ve talked about before.

If you want to know more about them check here.

Operator SDK: Bootstrapping and Building

Understanding the inner workings of the Kubernetes API, compliantly to the OpenAPI standard, is not an easy task. We can say the same about creating controllers that run exactly like the native ones with all tools provided by the API machinery SIG and controller-runtime libraries, in order to facilitate the creation of the operator framework. Among the tools the operator framework provides is the operator-sdk command line tool. Let’s check how it helps us to quickly scaffold all the necessary tooling to concentrate only on the operator logic.

Initializing a new operator project:

$ mkdir myproject

$ cd myproject

$ operator-sdk init --domain mydomain.com --group myapp --kind MyApp --version v1alpha1

After running a go project folder will be scaffolded with the minimum elements to develop and build the operator.

.

├── Dockerfile

├── Makefile

├── PROJECT

├── bin

├── config

├── go.mod

├── go.sum

├── hack

└── main.go

We have our basic Dockerfile to build the operator, a Makefile with all automation necessary to test and build, the config folder where all yaml artifacts will live powered by Kustomize and the main.go where all begins with the manager that runs our controllers. To add a new API/CRD endpoint with a controller for our custom application we run the following for example:

$ operator-sdk create api \

--group=myapp \

--version=v1alpha1 \

--kind=MyApp \

--resource \

--controller

Now we have 2 new folders:

.

├── Dockerfile

├── Makefile

├── PROJECT

├── api

├── bin

├── config

├── controllers

├── go.mod

├── go.sum

├── hack

└── main.go

The folders api and controllers. And there we can find all the code automatically generated to begin the development process.

In the api we find:

$ tree -L 2 api

api

└── v1alpha1

├── groupversion_info.go

├── myapp_types.go

└── zz_generated.deepcopy.go

myapp_types.go will hold all the fields and elements for the application.

And finally on the controller side we have:

$ tree -L 2 controllers

controllers

├── myapp_controller.go

└── suite_test.go

And myapp_controller.go will hold all the controller logic for us.

The reconcile function will be ready for you to insert your code:

func (r *MyAppReconciler) Reconcile(req ctrl.Request) (ctrl.Result, error) {

_ = context.Background()

_ = r.Log.WithValues("myapp", req.NamespacedName)

// your logic here

return ctrl.Result{}, nil

}

To better understand this process if you really want to go in I strongly recommend two tutorials:

The kubebuilder book. Kubebuilder just merged into operator-sdk and a good part of the logic inside comes from the kubebuilder project. So to understand deeper the Kubernetes API and controllers logic this is probably the best place to start.

Finally, I totally recommend taking a look on the operator-sdk website where you can also find a lot of resources and examples. https://sdk.operatorframework.io

Operator Lifecycle Manager: Publishing Operators

Another key project in the operator-framework is the Operator Lifecycle Manager that acts as your software catalog presenting to kubernetes a software as a service application where all publicly published operators can be installed from. Check the project here and more information on the https://operatorhub.io.

Conclusion

We talked about what are Kubernetes operators and how they are made of 2 basic but powerful pieces that are the Kubernetes Custom Resources and Controllers. We touched a little bit on the operator-sdk that helps us scaffolding all the code to easily begin developing Kubernetes native applications that will talk to the api and control our custom resources representing our application inside the cluster. We suggested checking the Kubebuilder book and the operator-sdk docs on the website. And finally, we pointed out that the operator lifecycle manager is the official catalog where all the public operators can be found.