Guest post by DatenLord

Introduction

In the early prototype phase of Xline, we used in-memory storage for data persistence. While this simplified the complexity of the Xline prototype design and speeded up the development and iteration of the project, it also had significant consequences: since the data was stored in memory, the recovery of node data after a process crash relied on pulling the full data from other healthy nodes, resulting in longer recovery times.

With this consideration in mind, Xline introduced a Persistent Storage Layer in its latest release v0.3.0 to persist data to disk and shield upper-layer callers from irrelevant low-level details.

Selection of Storage Engines

Currently, mainstream storage engines in the industry can be broadly categorized into B+ Tree-based storage engines and LSM Tree-based storage engines. Each has its own advantages and disadvantages.

Analysis of B+ Tree Read and Write Amplification

When reading data from B+ Tree, we need to first search along the root node, and then move down the index until we finally reach the bottom leaf node. Each access corresponds to one disk IO. Similarly, when writing data, the search starts from the root node and goes down to the appropriate leaf node for data insertion.

To facilitate the analysis, let’s make the following assumption: the block size of the B+ Tree is denoted as B, so each internal node contains O(B) child nodes, and each leaf node contains O(B) data entries. Assuming the size of the dataset is N, the height of the B+ Tree is approximately ![]()

Write Amplification: Each insert operation in the B+ Tree writes data to a leaf node, regardless of the actual size of the data. This means that each insert operation requires writing a block of size B, resulting in a write amplification of O(B).

Read Amplification: A single query in the B+ Tree requires traversing from the root node to a specific leaf node, resulting in a number of I/O operations equal to the height of the tree, which is approximately O(log_B(N/B)). Thus, the read amplification is O(log_B(N/B)).

LSM Tree Read and Write Amplification Analysis

In LSM Tree, when data is written, it is first written to an in-memory file called the memtable (Level 0) in an append-only manner. When the memtable reaches a certain size, it is converted into an immutable memtable and merged into the next level. For data retrieval, the search starts in the memtable, and if the search fails, it proceeds to search in lower levels until the element is found. LSM Tree often utilizes Bloom Filters to optimize read operations by filtering out elements that do not exist in the database.

Assuming the dataset size is N, the amplification factor is k, and the minimum file size in each level is B, with each level having the same file size as B but a different number of files.

Write Amplification: Assuming we write a record, it will be compacted to the next level after being written k times in the current level. Therefore, the average write amplification per level is ![]()

. There are ![]()

levels in total, so the write amplification is ![]()

Read Amplification: In the worst-case scenario, data is compacted to the last level, and a binary search is required at each level until the data is found at the last level.

For the highest level, ![]() , level , with data size O(N), a binary search requires

, level , with data size O(N), a binary search requires

disk read operations. For the next level, level, ![]() , with data size

, with data size ![]() , a binary search requires

, a binary search requires ![]() disk read operations. For

disk read operations. For ![]() with data size

with data size ![]() , a binary search requires

, a binary search requires ![]()

disk read operations.

…

Continuing this pattern, the final read amplification can be calculated as R =

Summary

From the analysis of read and write amplification, it can be concluded that B+ Tree-based storage engines are more suitable for scenarios with more reads and fewer writes, while LSM Tree-based storage engines are more suitable for scenarios with more writes and fewer reads.

As an open-source distributed KV storage software written in Rust, Xline needs to consider the following factors when selecting a persistent storage engine:

- In terms of Performance: Storage engines often become one of the performance bottlenecks in a system, so it is necessary to choose a high-performance storage engine. High-performance storage engines are typically implemented in high-performance languages, preferably with asynchronous implementations. Rust language is the first choice, followed by C/C++.

2. From a development perspective: Prioritize the implementation in Rust language to reduce additional development work at the current stage.

3. From a maintenance perspective:

Consider the supporters behind the engine, with priority given to large commercial companies and open-source communities.

It should be widely used in the industry to facilitate learning from experiences in debugging and tuning processes.

It should have high visibility and popularity (GitHub stars) to attract excellent contributors.

4. From a functional perspective: The storage engine should provide transactional semantics, support basic KV operations, and batch processing operations.

The priority order of requirements is: Functionality > Maintenance > =Performance > Development.

We conducted research on several open-source embedded databases, including Sled, ForestDB, RocksDB, Bbolt, and Badger. Among them, only RocksDB fulfilled all four requirements mentioned earlier. RocksDB, implemented and open-sourced by Facebook, has been widely adopted in the industry with good production practices. It also maintains a stable release cycle and perfectly covers our functional requirements.

Xline primarily serves the consistency metadata management across cloud data centers, where the workload is predominantly read-intensive with fewer writes. Some readers may wonder why we chose RocksDB even though it is an LSM Tree-based storage engine, which is more suitable for write-intensive, read-light scenarios.

Indeed, in theory, the most suitable storage engine should be based on B+ Trees. However, considering that B+ Tree-based embedded databases like Sled and ForestDB lack extensive production practices and their version maintenance has stalled, we made a trade-off and selected RocksDB as the storage backend for Xline. Additionally, we designed the Persistent Storage Layer with good interface separation and encapsulation to minimize the cost of changing the storage engine in the future, considering the possibility of more suitable storage engines becoming available.

Design and Implementation of the Persistent Storage Layer

Before discussing the design and implementation of the persistent storage layer, it is important to clarify our expectations and requirements for persistent storage:

- As mentioned earlier, after considering the trade-offs, we have chosen RocksDB as the backend storage engine for Xline. However, we cannot rule out the possibility of replacing this storage engine in the future. Therefore, the design of the StorageEngine should adhere to the Open-Closed Principle (OCP) and support configurability and easy replacement.

- We need to provide a basic key-value (KV) interface for the upper-layer users.

- A comprehensive recovery mechanism needs to be implemented.

Overall Architecture and Write Flow

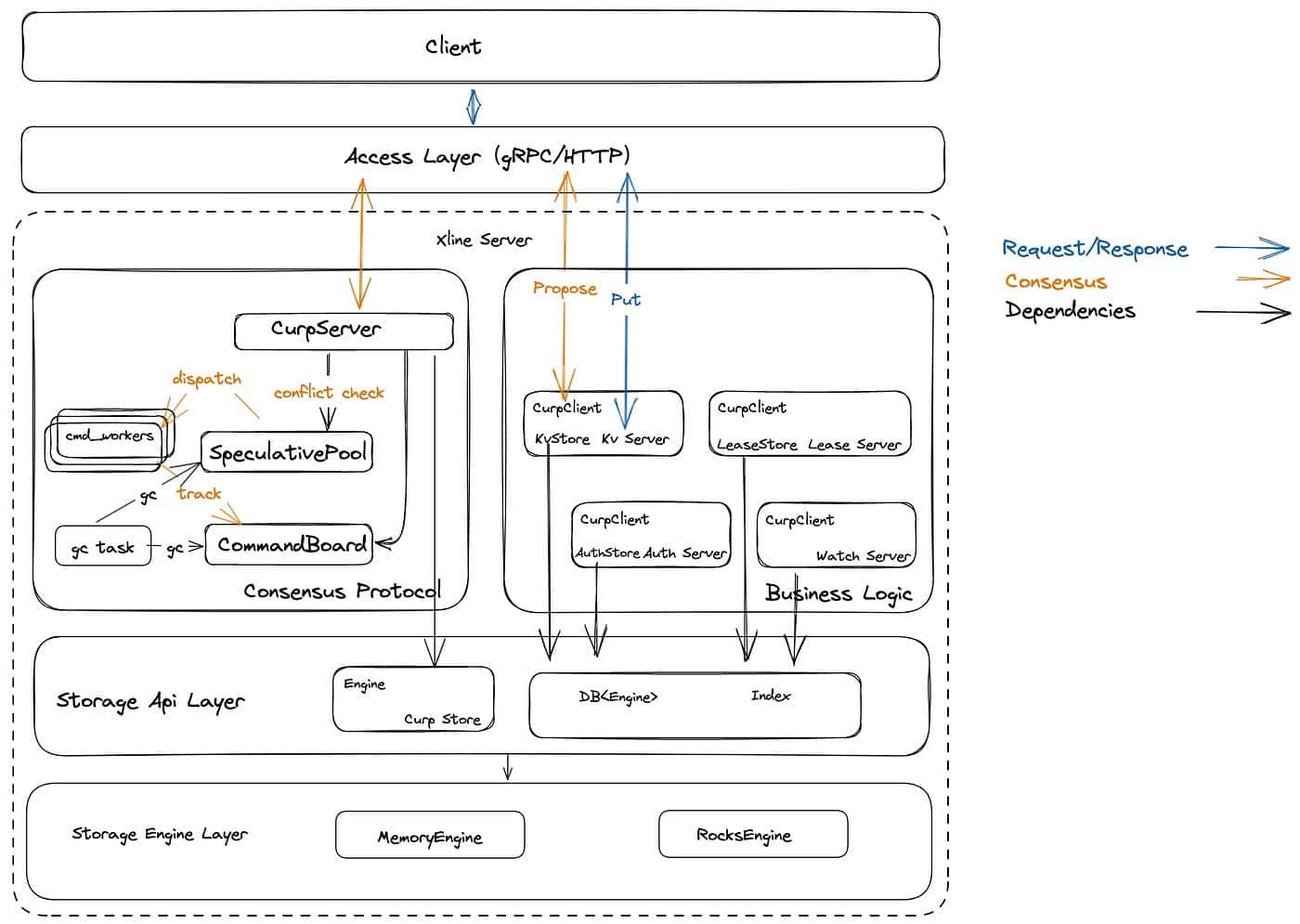

Let’s first take a look at the current overall architecture of Xline, as shown in the following diagram:

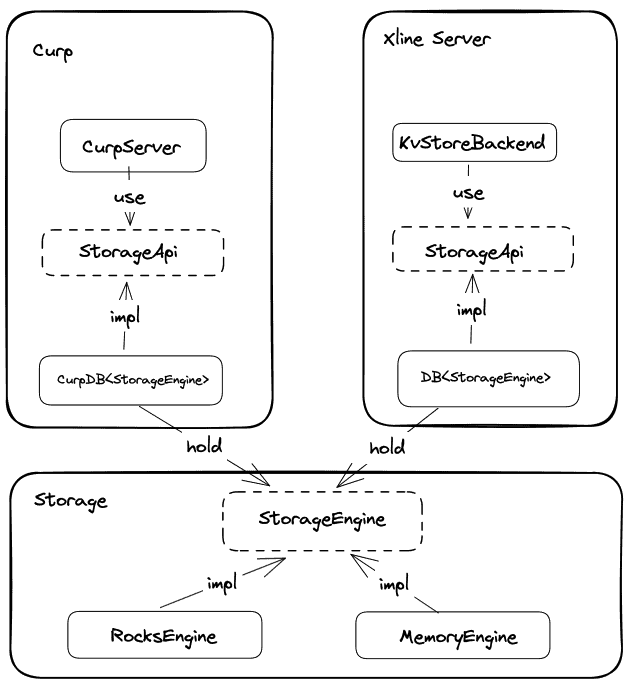

From top to bottom, the overall architecture of Xline can be divided into the access layer, consensus module, business logic module, storage API layer, and storage engine layer. The storage API layer is responsible for providing business-related StorageApi to both the business module and the consensus module, while abstracting the implementation details of the underlying storage engine. The storage engine layer is responsible for the actual data persistence operations.

Let’s take a PUT request as an example to understand the data writing process. When a client initiates a PUT request to the Xline Server, the following events occur:

- The KvServer receives the PutRequest from the client and performs validity checks. Once the request passes the checks, it sends a propose RPC request to the Curp Server using its own CurpClient.

- Upon receiving the Propose request, the Curp Server first enters the fast path flow. It stores the command from the request in the Speculative Executed Pool (aka. spec_pool) to determine if it conflicts with any existing commands in the pool. If there is a conflict, it returns ProposeError::KeyConflict and waits for the slow path to complete. Otherwise, it continues with the current fast path.

- In the fast path, if a command is neither conflicting nor duplicated, it notifies the background cmd_worker for execution through a specific channel. Once the cmd_worker starts executing the command, it stores the corresponding command in the CommandBoard to track the execution progress.

- When consensus is reached among multiple nodes in the cluster, the state machine log is committed and persisted in the CurpStore. Finally, the log is applied, triggering the corresponding CommandExecutor in the business module. Each server’s store module is responsible for persisting the actual data to the backend database using the DB interface during the apply process.

Interface Design

The following diagram illustrates the relationships between the StorageApi and StorageEngine traits, as well as their corresponding data structures.

Storage Engine Layer

The Storage Engine Layer primarily defines the StorageEngine trait and related errors. Definition of StorageEngine Trait (engine/src/engine_api.rs):

/// Write operation

#[non_exhaustive]

#[derive(Debug)]

pub enum WriteOperation<'a> {

/// `Put` operation

Put { table: &'a str, key: Vec<u8>, value: Vec<u8> },

/// `Delete` operation

Delete { table: &'a str, key: &'a [u8] },

/// Delete range operation, it will remove the database entries in the range [from, to)

DeleteRange { table: &'a str, from: &'a [u8], to: &'a [u8] },

}

/// The `StorageEngine` trait

pub trait StorageEngine: Send + Sync + 'static + std::fmt::Debug {

/// Get the value associated with a key value and the given table

///

/// # Errors

/// Return `EngineError::TableNotFound` if the given table does not exist

/// Return `EngineError` if met some errors

fn get(&self, table: &str, key: impl AsRef<[u8]>) -> Result<Option<Vec<u8>>, EngineError>;

/// Get the values associated with the given keys

///

/// # Errors

/// Return `EngineError::TableNotFound` if the given table does not exist

/// Return `EngineError` if met some errors

fn get_multi(

&self,

table: &str,

keys: &[impl AsRef<[u8]>],

) -> Result<Vec<Option<Vec<u8>>>, EngineError>;

/// Get all the values of the given table

/// # Errors

/// Return `EngineError::TableNotFound` if the given table does not exist

/// Return `EngineError` if met some errors

#[allow(clippy::type_complexity)] // it's clear that (Vec<u8>, Vec<u8>) is a key-value pair

fn get_all(&self, table: &str) -> Result<Vec<(Vec<u8>, Vec<u8>)>, EngineError>;

/// Commit a batch of write operations

/// If sync is true, the write will be flushed from the operating system

/// buffer cache before the write is considered complete. If this

/// flag is true, writes will be slower.

///

/// # Errors

/// Return `EngineError::TableNotFound` if the given table does not exist

/// Return `EngineError` if met some errors

fn write_batch(&self, wr_ops: Vec<WriteOperation<'_>>, sync: bool) -> Result<(), EngineError>;

}Related Error Definitions

#[non_exhaustive]

#[derive(Error, Debug)]

pub enum EngineError {

/// Met I/O Error during persisting data

#[error("I/O Error: {0}")]

IoError(#[from] std::io::Error),

/// Table Not Found

#[error("Table {0} Not Found")]

TableNotFound(String),

/// DB File Corrupted

#[error("DB File {0} Corrupted")]

Corruption(String),

/// Invalid Argument Error

#[error("Invalid Argument: {0}")]

InvalidArgument(String),

/// The Underlying Database Error

#[error("The Underlying Database Error: {0}")]

UnderlyingError(String),

}MemoryEngine (engine/src/memory_engine.rs) and RocksEngine (engine/src/rocksdb_engine.rs) implement the StorageEngine trait. MemoryEngine is mainly used for testing purposes, while the definition of RocksEngine is as follows:

/// `RocksDB` Storage Engine

#[derive(Debug, Clone)]

pub struct RocksEngine {

/// The inner storage engine of `RocksDB`

inner: Arc<rocksdb::DB>,

}

/// Translate a `RocksError` into an `EngineError`

impl From<RocksError> for EngineError {

#[inline]

fn from(err: RocksError) -> Self {

let err = err.into_string();

if let Some((err_kind, err_msg)) = err.split_once(':') {

match err_kind {

"Corruption" => EngineError::Corruption(err_msg.to_owned()),

"Invalid argument" => {

if let Some(table_name) = err_msg.strip_prefix(" Column family not found: ") {

EngineError::TableNotFound(table_name.to_owned())

} else {

EngineError::InvalidArgument(err_msg.to_owned())

}

}

"IO error" => EngineError::IoError(IoError::new(Other, err_msg)),

_ => EngineError::UnderlyingError(err_msg.to_owned()),

}

} else {

EngineError::UnderlyingError(err)

}

}

}

impl StorageEngine for RocksEngine {

/// omit some code

}StorageApi Layer

Business Module

Definition of StorageApi in the business module:

/// The Stable Storage Api

pub trait StorageApi: Send + Sync + 'static + std::fmt::Debug {

/// Get values by keys from storage

fn get_values<K>(&self, table: &'static str, keys: &[K]) -> Result<Vec<Option<Vec<u8>>>, ExecuteError>

where

K: AsRef<[u8]> + std::fmt::Debug;

/// Get values by keys from storage

fn get_value<K>(&self, table: &'static str, key: K) -> Result<Option<Vec<u8>>, ExecuteError>

where

K: AsRef<[u8]> + std::fmt::Debug;

/// Get all values of the given table from the storage

fn get_all(&self, table: &'static str) -> Result<Vec<(Vec<u8>, Vec<u8>)>, ExecuteError>;

/// Reset the storage

fn reset(&self) -> Result<(), ExecuteError>;

/// Flush the operations to storage

fn flush_ops(&self, ops: Vec<WriteOp>) -> Result<(), ExecuteError>;

}In the business module, DB (xline/src/storage/db.rs) is responsible for converting StorageEngine into StorageApi for upper-level calls. Its definition is as follows:

/// Database to store revision to kv mapping

#[derive(Debug)]

pub struct DB<S: StorageEngine> {

/// internal storage of `DB`

engine: Arc<S>,

}

impl<S> StorageApi for DB<S>

where

S: StorageEngine

{

/// omit some code

}In the business module, different servers have their own Store backends, and the core data structure is the DB in the StorageApi Layer.

Consensus Module

The StorageApi definition of the Curp module is located in curp/src/server/storage/mod.rs.

/// Curp storage api

#[async_trait]

pub(super) trait StorageApi: Send + Sync {

/// Command

type Command: Command;

/// Put `voted_for` in storage, must be flushed on disk before returning

async fn flush_voted_for(&self, term: u64, voted_for: ServerId) -> Result<(), StorageError>;

/// Put log entries in the storage

async fn put_log_entry(&self, entry: LogEntry<Self::Command>) -> Result<(), StorageError>;

/// Recover from persisted storage

/// Return `voted_for` and all log entries

async fn recover(

&self,

) -> Result<(Option<(u64, ServerId)>, Vec<LogEntry<Self::Command>>), StorageError>;

}RocksDBStorage (curp/src/server/storage/rocksdb.rs) is the CurpStore mentioned in the previous architectural diagram. It is responsible for converting StorageApi into underlying RocksEngine operations.

/// `RocksDB` storage implementation

pub(in crate::server) struct RocksDBStorage<C> {

/// DB handle

db: RocksEngine,

/// Phantom

phantom: PhantomData<C>,

}

#[async_trait]

impl<C: 'static + Command> StorageApi for RocksDBStorage<C> {

/// Command

type Command = C;

/// omit some code

}Implementation Details

Data Views

With the introduction of the Persistent Storage Layer, Xline uses logical tables to separate different namespaces. Currently, these tables correspond to Column Families in the underlying RocksDB.

The following tables are currently available:

- curp: Stores persistent information related to curp, including log entries, voted_for, and corresponding term information.

- lease: Stores granted lease information.

- kv: Stores key-value information.

- auth: Stores the enablement status of auth in Xline and the corresponding enable revision.

- user: Stores user information added in Xline.

- role: Stores role information added in Xline.

- meta: Stores the current applied log index.

Scalability

Xline separates storage-related operations into two different traits, StorageEngine and StorageApi, and distributes them across two different layers to isolate changes. The StorageEngine trait provides a mechanism, while the StorageApi is defined by upper-level modules, allowing different modules to have their own definitions and implement specific storage strategies. The CurpStore and DB in the StorageApi layer are responsible for implementing the conversion between these two traits. Since the upper-level callers do not directly depend on the underlying Storage Engine, changing the storage engine later would not require extensive modifications to the code of the upper-level modules.

Recovery Process

For the recovery process, two important aspects need to be considered: what data to recover and when to perform the recovery. Let’s first examine the data involved in recovery between different modules.

Consensus Module

In the consensus module, since RocksDBStorage is exclusive to Curp Server, the recovery process can be directly added to the respective StorageApi trait. The specific implementation is as follows:

#[async_trait]

impl<C: 'static + Command> StorageApi for RocksDBStorage<C> {

/// Command

type Command = C;

/// omit some code

async fn recover(

&self,

) -> Result<(Option<(u64, ServerId)>, Vec<LogEntry<Self::Command>>), StorageError> {

let voted_for = self

.db

.get(CF, VOTE_FOR)?

.map(|bytes| bincode::deserialize::<(u64, ServerId)>(&bytes))

.transpose()?;

let mut entries = vec![];

let mut prev_index = 0;

for (k, v) in self.db.get_all(CF)? {

// we can identify whether a kv is a state or entry by the key length

if k.len() == VOTE_FOR.len() {

continue;

}

let entry: LogEntry<C> = bincode::deserialize(&v)?;

#[allow(clippy::integer_arithmetic)] // won't overflow

if entry.index != prev_index + 1 {

// break when logs are no longer consistent

break;

}

prev_index = entry.index;

entries.push(entry);

}

Ok((voted_for, entries))

}

}For the consensus module, during the recovery process, the voted_for value and the corresponding term are first loaded from the underlying database. This is a security guarantee for the consensus algorithm to prevent voting twice within the same term. Subsequently, the corresponding log entries are loaded.

Business Module

For the business module, different servers have different stores and rely on the mechanisms provided by the underlying DB. Therefore, the recovery process is not defined in the StorageApi trait but exists as separate methods in LeaseStore (xline/src/storage/lease_store/mod.rs), AuthStore (xline/src/storage/auth_store/store.rs), and KvStore (xline/src/storage/kv_store.rs).

/// Lease store

#[derive(Debug)]

pub(crate) struct LeaseStore<DB>

where

DB: StorageApi,

{

/// Lease store Backend

inner: Arc<LeaseStoreBackend<DB>>,

}

impl<DB> LeaseStoreBackend<DB>

where

DB: StorageApi,

{

/// omit some code

/// Recover data form persistent storage

fn recover_from_current_db(&self) -> Result<(), ExecuteError> {

let leases = self.get_all()?;

for lease in leases {

let _ignore = self

.lease_collection

.write()

.grant(lease.id, lease.ttl, false);

}

Ok(())

}

}

impl<S> AuthStore<S>

where

S: StorageApi,

{

/// Recover data from persistent storage

pub(crate) fn recover(&self) -> Result<(), ExecuteError> {

let enabled = self.backend.get_enable()?;

if enabled {

self.enabled.store(true, AtomicOrdering::Relaxed);

}

let revision = self.backend.get_revision()?;

self.revision.set(revision);

self.create_permission_cache()?;

Ok(())

}

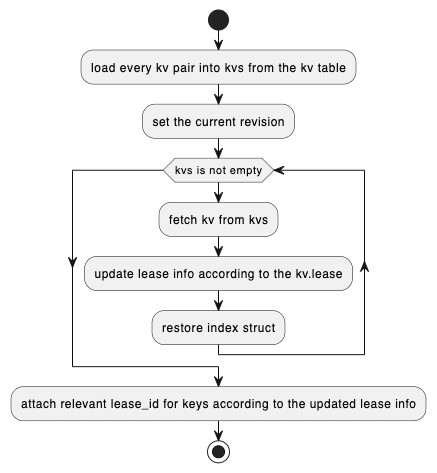

}Among them, the recovery logic for LeaseStore and AuthStore is relatively simple, and we won’t delve into it too much. Let’s focus on the recovery process of KvStore. The flowchart for its recovery process is as follows:

Recovery Timing

The recovery timing in Xline primarily occurs during the initial system startup. The recovery of the business module is prioritized, followed by the recovery of the consensus module. Since the recovery of KvStore depends on the recovery of LeaseStore, the recovery of LeaseStore needs to take place before the recovery of KvStore. The corresponding code in xline/src/server/xline_server.rs is as follows:

impl<S> XlineServer<S>

where

S: StorageApi,

{

/// Start `XlineServer`

#[inline]

pub async fn start(&self, addr: SocketAddr) -> Result<()> {

// lease storage must recover before kv storage

self.lease_storage.recover()?;

self.kv_storage.recover().await?;

self.auth_storage.recover()?;

let (kv_server, lock_server, lease_server, auth_server, watch_server, curp_server) =

self.init_servers().await;

Ok(Server::builder()

.add_service(RpcLockServer::new(lock_server))

.add_service(RpcKvServer::new(kv_server))

.add_service(RpcLeaseServer::from_arc(lease_server))

.add_service(RpcAuthServer::new(auth_server))

.add_service(RpcWatchServer::new(watch_server))

.add_service(ProtocolServer::new(curp_server))

.serve(addr)

.await?)

}The recovery process of the consensus module (curp/src/server/curp_node.rs) is as follows, with the function call chain: XlineServer::start -> XlineServer::init_servers -> CurpServer::new -> CurpNode::new

// utils

impl<C: 'static + Command> CurpNode<C> {

/// Create a new server instance

#[inline]

pub(super) async fn new<CE: CommandExecutor<C> + 'static>(

id: ServerId,

is_leader: bool,

others: HashMap<ServerId, String>,

cmd_executor: CE,

curp_cfg: Arc<CurpConfig>,

tx_filter: Option<Box<dyn TxFilter>>,

) -> Result<Self, CurpError> {

// omit some code

// create curp state machine

let (voted_for, entries) = storage.recover().await?;

let curp = if voted_for.is_none() && entries.is_empty() {

Arc::new(RawCurp::new(

id,

others.keys().cloned().collect(),

is_leader,

Arc::clone(&cmd_board),

Arc::clone(&spec_pool),

uncommitted_pool,

curp_cfg,

Box::new(exe_tx),

sync_tx,

calibrate_tx,

log_tx,

))

} else {

info!(

"{} recovered voted_for({voted_for:?}), entries from {:?} to {:?}",

id,

entries.first(),

entries.last()

);

Arc::new(RawCurp::recover_from(

id,

others.keys().cloned().collect(),

is_leader,

Arc::clone(&cmd_board),

Arc::clone(&spec_pool),

uncommitted_pool,

curp_cfg,

Box::new(exe_tx),

sync_tx,

calibrate_tx,

log_tx,

voted_for,

entries,

last_applied.numeric_cast(),

))

};

// omit some code

Ok(Self {

curp,

spec_pool,

cmd_board,

shutdown_trigger,

storage,

})

}Performance Evaluation

In v0.3.0, except for introducing the persistent storage layer, we also conducted significant refactoring on certain parts of CURP. After completing the refactoring and adding new features, we recently passed the validation test and integration test. The performance testing information has already been released in Xline v 0.4.0.

Xline GitHub :https://github.com/datenlord/Xline

Xline official website:www.xline.cloud