The Reason for Implementing Interval Trees

In a recent refactoring of Xline, we identified a performance bottleneck caused by two data structures on the critical path: the Speculative Pool and the Uncommitted Pool. These two data structures are used for conflict detection in CURP. Specifically, the protocol requires for each processed command, it is necessary to find all the commands that conflict with the current command.

For instance, in the KV operations put/get_range/delete_range, we need to consider the possible conflicts between these operations. Since each KV operation covers a range of keys, the problem becomes checking whether a given range of keys intersects with any key ranges in the pool. A plain traversal of the entire set results in a time complexity of O(n) for each query, which reduces efficiency and leads to performance bottlenecks.

To address this problem, we need to introduce an interval tree data structure. Interval trees support efficient insertion, deletion and query operations on overlapping intervals, all of which can be completed in O(log(n)) time. Therefore, we can use the interval tree to maintain a collection of key ranges.

Introduction to Interval Tree Implementation

The interval tree implementation in Xline is based on Introduction to Algorithms (3rd ed.), which extends the self-balancing binary search tree.

The interval tree is based on a binary balanced tree (e.g., a red-black tree), and the interval itself is used as the key. For an interval [low, high], we first sort the intervals by their low values, and then by their high values if the low values are the same, establishing a total order relationship for the set of intervals. If duplicate intervals are not handled, sorting by high values is unnecessary. Additionally, for each node in the balanced tree, we maintain the maximum value of high in the subtree rooted at this node, denoted as max.

Keep reading

- Understand the Xline command deduplication mechanism

- A look at who’s using Xline and what they’re doing with it

- Analyzing Xline Jepsen tests

- Register for KubeCon + CloudNativeCon North America 2024 today

Insertion/Deletion

Same as insertion/deletion in red-black tree, the worst time complexity is O(log(n)).

Query Overlap

Given an interval i, we need to query the current tree to see if any intervals in the tree overlap with i.

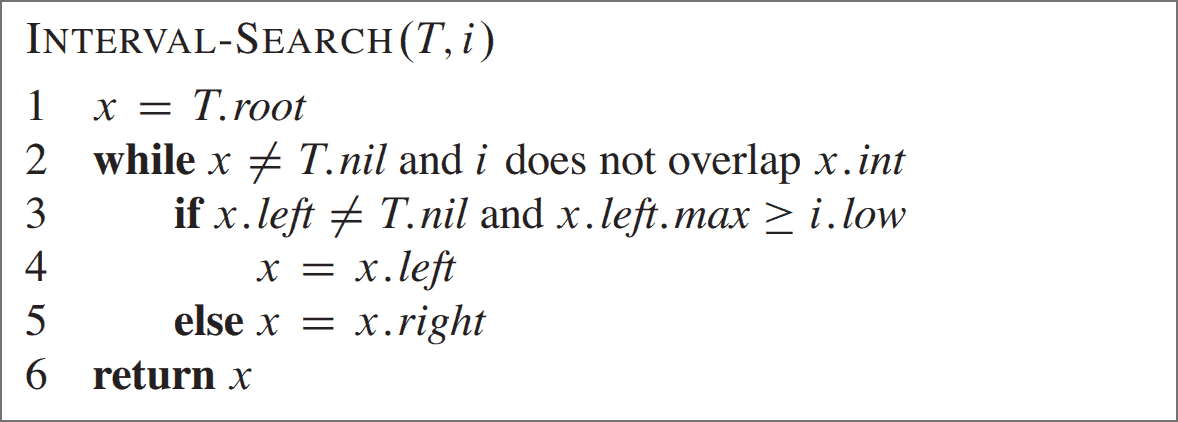

The pseudo-code given in Introduction to Algorithms is as follows

With the definition of max, the solution to this problem becomes straightforward: for a subtree T_x rooted at x, if i does not intersect x_i, then i must lie to either the left or right of x_i.

- If i is on the left side of x_i, then we can rule out the right subtree, because i.high is smaller than x_i.low.

- if i is on the right side of x_i: In this case, we can’t rule out the left subtree, because the intervals of nodes in the left subtree may still intersect i. This is where max comes in handy.

- If the maximum value of high in x’s left subtree is still less than i.low, then we can ignore x’s left subtree.

- If the maximum value of high in x’s left subtree is greater than or equal to i.low, then there must be intersecting intervals in x’s left subtree because all the lows in x’s left subtree are less than x_i.low, and i is on the right side of x_i, so all the lows in x’s left subtree are less than i.low, so there must be an intersection.

The above points can validate the correctness of the pseudo-code, and from the code we can infer that the worst-case time complexity of the query is O(log(n)).

Implementing Interval Trees with Safe Rust

Difficulty

To construct an interval tree, we first need to implement a red-black tree. In a red-black tree, each node must reference its parent node, which requires multiple ownership of a single node instance.

Rc<RefCell<T>>

I initially attempted to use Rust’s most common multi-ownership implementation, Rc<RefCell<T>>, with a tree node structure similar to the following code.

struct Node<T, V> {

left: Option<NodeRef<T, V>>,

right: Option<NodeRef<T, V>>,

parent: Option<NodeRef<T, V>>,

...

}

struct NodeRef<T, V>(Rc<RefCell<Node<T, V>>>);The data structure definition appears straightforward, but in practice it’s quite cumbersome to use, because RefCell requires the user to explicitly call borrow, or borrow_mut, requiring me to create numerous helper functions to simplify the implementation. Here are some examples.

impl<T, V> NodeRef<T, V> {

fn left<F, R>(&self, op: F) -> R

where

F: FnOnce(&NodeRef<T, V>) -> R,

{

op(self.borrow().left())

}

fn parent<F, R>(&self, op: F) -> R

where

F: FnOnce(&NodeRef<T, V>) -> R,

{

op(self.borrow().parent())

}

fn set_right(&self, node: NodeRef<T, V>) {

let _ignore = self.borrow_mut().right.replace(node);

}

fn set_max(&self, max: T) {

let _ignore = self.borrow_mut().max.replace(max);

}

...

}RefCell is not ergonomic to use, but even worse, we need to use a lot of Rc::clone in our code, because when traversing a tree node from the top down, we need to hold the owned type of a node, not a reference. For example, in the previously mentioned INTERVAL-SEARCH operation, every time x = x.left or x = x.right, we first need to borrow x itself, and then assign it a value. So we need to get the owned type of the left (or right) node first, and then update x to the new value. This leads to a lot of reference counting overhead.

How substantial is this overhead? I benchmarked our implementation using random data insertion and deletion on my local setup, which includes an Intel 13600KF processor with DDR4 memory.

test bench_interval_tree_insert_100 ... bench: 9,821 ns/iter (+/- 263)

test bench_interval_tree_insert_1000 ... bench: 215,362 ns/iter (+/- 6,536)

test bench_interval_tree_insert_10000 ... bench: 2,999,694 ns/iter (+/- 134,979)

test bench_interval_tree_insert_remove_100 ... bench: 18,395 ns/iter (+/- 750)

test bench_interval_tree_insert_remove_1000 ... bench: 385,858 ns/iter (+/- 7,659)

test bench_interval_tree_insert_remove_10000 ... bench: 5,465,355 ns/iter (+/- 114,735)Using the same data and environment, compare it to the golang interval tree implementation of etcd.

BenchmarkIntervalTreeInsert100-20 123747 12250 ns/op

BenchmarkIntervalTreeInsert1000-20 7119 189613 ns/op

BenchmarkIntervalTreeInsert10_000-20 340 3237907 ns/op

BenchmarkIntervalTreeInsertRemove100-20 24584 45579 ns/op

BenchmarkIntervalTreeInsertRemove1000-20 344 3462977 ns/op

BenchmarkIntervalTreeInsertRemove10_000-20 3 358284695 ns/opAs you can see, our Rust implementation has no advantage, and even slows down insertion operations in some cases. (Note: there appears to be an issue with etcd’s node deletion implementation. Observe the increase in the number of nodes from 1000->10000, the complexity may not align with O(log(n))).

Thread Safety Issues

Even if we grudgingly accept the performance, a more serious problem surfaces: Rc<RefCell<T>> cannot be used in a multi-threaded environment! Since Xline is built on top of Rust’s Tokio runtime, it needs to share a single instance of the interval tree across multiple threads. Unfortunately, Rc itself is !Send, because reference counting inside Rc is incremented/decremented in a non-atomic way. This then results in the entire interval tree data structure not being sent to other threads. Unless we spawn a dedicated thread and communicate through a channel, we can’t use it in a multi-threaded environment.

Other Smart Pointers

So we need to consider other smart pointers to resolve this issue. A natural idea is to use Arc<RefCell<T>>. However, RefCell itself is !Sync, because its borrow checking can only be used within a single thread and cannot be shared across multiple threads at the same time, and Arc<T>> is Send if and only if T is Sync, because Arc itself allows cloning.

Arc<Mutex<T>> ?

In a multi-threaded environment, multiple ownership can only be achieved using Arc<Mutex<T>>. However, this is clearly an anti-pattern for our use case, which requires a mutex on each node, and with hundreds of thousands or even millions of nodes in the tree, this is impractical.

QCell

After using conventional methods to no avail, we tried to use a crate called qcell, a multi-threaded alternative to RefCell. The author ingeniously addressed the issue of borrowing checks under multiple ownership.

QCell design

Since the design of qcell is formally demonstrated in the GhostCell paper, I will introduce the design in the GhostCell paper here.

In Rust, permissions to manipulate data are tied to the data itself, i.e., you must first own the data in order to modify its state. Specifically, to modify the data T, you either need to have a T itself, or you need to have an &mut T.

The concept of GhostCell’s design is to separate permissions to manipulate data from the data itself, so that for a piece of data, the data T itself is a type, and its permissions are also of a specific type, denoted P_t. This design is more flexible than Rust’s existing design because it is possible for an instance of a permission type to have permission over a collection of data, i.e., a single P_t can have multiple T’s. Under this design, as long as the permission instance itself is thread-safe, the data collection it manages is also thread-safe.

To use this in a qcell, first create a QCellOwner to represent the permissions, and a QCell<T> to represent the stored data.

let mut owner = QCellOwner::new();

let item = Arc::new(QCell::new(&owner, Vec::<u8>::new()));

owner.rw(&item).push(0);QCellOwner has read/write access to the QCells registered to it (via QCellOwner::rwor QCellOwner::ro ), so as long as QCellOwner is thread-safe, the data in the QCells are thread-safe too. Here QCellOwner itself is Send + Sync, and QCell can be Send + Sync as long as T satisfies.

impl<T: ?Sized + Send> Send for QCell<T>

impl<T: ?Sized + Send + Sync> Sync for QCell<T>Using QCell

Thanks to its design, QCell has a very low overhead (I won’t go into the details here) because it leverages the Rust type system so that borrow checking is done at compile time, whereas RefCell checks at runtime, so using QCell not only allows you to use it in multi-threaded environments, but also gives you a performance boost.

The next step is to apply QCell to our tree implementation. Since QCell only provides internal mutability, in order to be able to use multiple ownerships, we also need to have Arc, which looks like this.

pub struct IntervalTree {

node_owner: QCellOwner,

...

}

struct NodeRef<T, V>(Arc<QCell<Node<T, V>>>);Looking good, but how’s the performance?

test bench_interval_tree_insert_100 ... bench: 41,486 ns/iter (+/- 71)

test bench_interval_tree_insert_1000 ... bench: 586,854 ns/iter (+/- 13,947)

test bench_interval_tree_insert_10000 ... bench: 7,726,849 ns/iter (+/- 102,820)

test bench_interval_tree_insert_remove_100 ... bench: 75,569 ns/iter (+/- 325)

test bench_interval_tree_insert_remove_1000 ... bench: 1,135,232 ns/iter (+/- 7,539)

test bench_interval_tree_insert_remove_10000 ... bench: 15,686,474 ns/iter (+/- 194,385)Comparing the results of the previous tests, the performance drops by a factor of 1–3. This indicates that the biggest overhead is not the cell itself, but the reference counting, and in our interval tree case, using Arc is much slower than Rc.

An alternative to using Arc would be arena allocation, which allocates memory for all objects at once and deallocates them all at once. However, this approach is unsuitable for a tree data structure because we need to allocate and deallocate node memory dynamically.

Array Analog Pointers

Performance tests show that our attempts at smart pointers fail. Using smart pointers to implement tree structures within the Rust ownership model results in poor performance.

So can we implement it without using pointers? A natural idea is to use arrays to emulate pointers.

Our tree structure is redesigned as follows.

pub struct IntervalTree {

nodes: Vec<Node>,

...

}

pub struct Node {

left: Option<u32>,

right: Option<u32>,

parent: Option<u32>,

...

}As you can see, the advantage of arrays in Rust is that you don’t need to own a node, you just need to keep track of the index. Each time a new node is inserted, it is pushed one node after the nodes, and its index is nodes.len() — 1.

Insertion is straightforward, but what about node deletion? A naive approach would be nulling the corresponding node in the Vec, then we are left with a “hole” in our Vec. This requires maintaining extra states to keep track of this hole, so that we can reuse it for the next insertion. Moreover, this approach makes it difficult to reclaim the space of the nodes in the Vec, even if most of the nodes have already been deleted.

So, how do we solve this issue? Inspired by the method used in petgraph, we can swap the node to be removed with the last node in the Vec before deleting it. This way, we can efficiently reclaim memory. Note that we also need to update the pointer to the node associated with the last node, since its position has changed. In the petgraph implementation, this operation could be time-consuming because a node may be connected to any number of other nodes. However, in our tree structure, we only need to update the parent, left child, and right child pointers of this node, making this an O(1) operation. This efficiently solves the node deletion problem.

Let’s benchmark our new implementation:

test bench_interval_tree_insert_100 ... bench: 3,333 ns/iter (+/- 87)

test bench_interval_tree_insert_1000 ... bench: 85,477 ns/iter (+/- 3,552)

test bench_interval_tree_insert_10000 ... bench: 1,406,707 ns/iter (+/- 20,796)

test bench_interval_tree_insert_remove_100 ... bench: 7,157 ns/iter (+/- 69)

test bench_interval_tree_insert_remove_1000 ... bench: 189,277 ns/iter (+/- 3,014)

test bench_interval_tree_insert_remove_10000 ... bench: 3,060,029 ns/iter (+/- 50,829)We can observe a huge performance gain with this implementation, about 1–2x faster than both the previous Rc<RefCell<Node>> approach and the golang implementation in etcd.

Using arrays to emulate pointers not only solves the ownership problem easily, but also makes it more cache friendly due to the contiguous memory layout of arrays, making it even more performant than using actual pointers.

Summarizing

At this point, we have successfully implemented a interval tree using safe Rust. Through the various attempts described above, we found that using reference-counting smart pointers to implement tree or graph data structures in Rust is ineffective due to their unsuitability for memory-intensive operations. In the future, if I need to use safe Rust to implement pointer-like data structures, I would prefer to use arrays rather than smart pointers.